A History of Man’s Best Friend

/We’ve all heard the phrase ‘man’s best friend’ in reference to dogs. Dogs are our working partners, guides, guards, and family, but how did that connection between canines and humans come about?

Dogs, as we know them in the modern sense, branched off from the wild wolves in modern Asia, Europe, and the Middle East about 25,000 to 38,000 years ago, toward the end of the last Ice Age. This time period means that these animals co-existed with man during his hunter-gatherer stage, immediately preceding the development of agriculture. Of all domesticated animals, dogs were the first to be domesticated in approximately 13,000 BCE, a full 4,000 years before the next domesticated animal, the sheep. Notably, the dog was the first species to have a reciprocal relationship with humans.

How did this change in relationship status move dogs and humans from competing hunters to partners on a common team? No one knows for sure, since this was long before recorded histories, but genetics and early art tell a convincing tale. It is most likely that wild dogs were attracted to cooking fires of men and the smell of roasting meat. They would also be drawn by the smell of discarded animal carcases and at first were likely raiders, pillaging any unattended or discarded meat. The key to this early relationship was the type of animals attracted to human societies: these animals were generally less aggressive and were likely the non-dominant pack members with a lower flight threshold—in other words, ideal animals for domestication. Genetically, this interaction coincided with a morphological change in the canine skull, specifically the development of a shorter snout with fewer, more crowded, and smaller teeth—all physical characteristics associated with reduced aggression.

The relationship between man and dog was commensal to begin, meaning that while it was opportunistic for the dogs, it didn’t affect the humans in any way. But their interaction became mutualistic—a relationship good for both species—as humans took advantage of the dogs’ specific skills in hunting and protection, and then adapted new skills such as herding.

An alternate theory suggests that dogs exploited an earlier mutation to be able to digest starches and carbohydrates, something wolves are not able to do. This change occurred just as man was discovering the advantages of agriculture, allowing the dogs to feed off scrap heaps more efficiently. Interestingly, humans adapted to starch digestion at nearly the same time in an intriguing twist of parallel evolution.

Over the centuries and millennia, selective breeding by humans developed dogs into the modern species we know today. Much of modern breeding revolves around appearance, however early domestication selected almost exclusively for behavioural traits. In fact, scientific studies show there was a genetic selection for adrenaline and noradrenaline pathways leading to tameness and a greater emotional response in the animals. This helped to create the domesticated, loyal, connected personalities we recognize in our dogs today.

Please join us next week as we come back looking at the role of working dogs from the Romans and Vikings onwards.

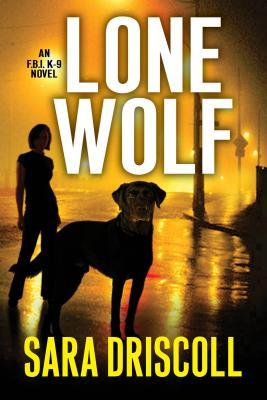

To celebrate the upcoming launch of LONE WOLF, Kensington is holding our first Goodreads giveaway! You can find it below. Be sure to enter for your chance to win an early copy months before it actually releases!

Goodreads Book Giveaway

Enter GiveawayPhoto credit: Fugzu and Elizabeth Tersigni

COMPLETE!

COMPLETE! Planning

Planning