Forensic Case Files: The Mystery of Philadelphia’s Mass Grave

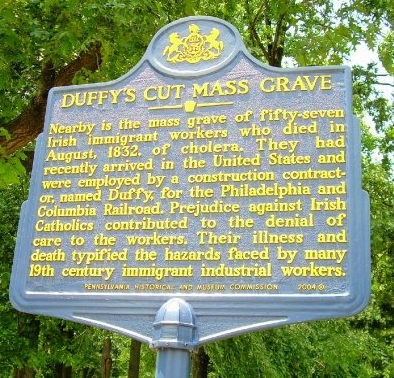

/In 1832, 57 Irish immigrants arrived in the United States, hired to lay track through Duffy’s Cut, a densely wooded area in what is now a Philadelphia suburb. But six weeks later, every immigrant was dead, their demise blamed on a local cholera epidemic. However, to the modern eye, these deaths are a mystery. Under normal circumstances, only 40 – 50% of untreated cholera cases perish, so why did they all die? The official story simply doesn't ring true. What really happened to the immigrants of Duffy’s Cut?

The story was originally brought to life by Immaculata University history professor William Watson and his brother Frank after reviewing records kept by their grandfather, a former employee of the Pennsylvania Railroad. The section of track in question had originally been built by the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad which later became part of the Pennsylvania Railroad. The brothers became suspicious at the overwhelming death toll and the lack of official death certificates files by the railroad. Historical records indicated that after the first few men were buried in individual graves, the remaining immigrants were buried together in a shallow ditch along the edge of the rail line. But where?

The Watson brothers set out to find that mass grave in 2004, but it wasn’t until 2007 when they first started to use ground penetrating radar that victims were found thirty feet below the surface. In 2009, the first remains were uncovered—two human skulls, a handful of teeth and 80 other bones. But almost immediately the fate of some of the men became clear from significant blunt force trauma to the skulls.

To date, the remains of five men and one woman have been recovered. Of the five men, three appear to have died not of cholera but of violent means, as indicated by bludgeoning, bullet wounds and axe trauma to the skulls. Unfortunately, the fate of the remaining men may remain a mystery as Amtrak, which owns the land, will not allow the excavation to continue because of safety concerns that it would venture too close to the active rail line. There are hopes of continuing at some point in the future, but, for now, the excavation is at an end.

Even the few remains recovered tell something of early 19th-century life. One of the recovered men has been identified as 18-year old John Ruddy of County Donegal in Ireland, based on both ship’s logs of the time as well as a characteristic dental trait—a missing first molar, a trait still shared by modern Ruddys. Muscle attachment points on the bones speak of a strong muscular build, and wear on the teeth show that he clenched them during heavy lifting. He had gum disease, but no cavities since, as a poor working man, he could not afford sugar. Once his identity is absolutely confirmed, his remains will be reburied in his family’s cemetery plot in Ireland.

Why did all the men die? In the early 1800s, prejudice against Catholics, and Irish Catholics in particular, was rampant. Sick immigrants seeking care were often turned away, leading to a higher death rate among that population. The Watson brothers theorize that local vigilante groups killed the remaining Irishmen in an attempt to curtail the cholera epidemic sweeping through the area.

In 2004, a historical marker was erected by the Pennsylvania Historical Society in memory of those who may never be recovered. The excavated remains of the four other men and one woman were laid to rest with full Catholic ceremony in West Laurel Hill Cemetery on March 9, 2012.

Photo credit: Duffy’s Cut Project and Duffy’s Cut Project Facebook Page

Complete!

Complete! Planning

Planning