Forensic Case Files: Cannibalism in Jamestown in the Early 17th Century

/ Jamestown, Virginia was settled on a swampy peninsula in 1607, making it America’s first permanent English colony. The soggy ground was considered un-farmable by the local Powhatan native tribes, and was rife with malaria-carrying mosquitos. But the lack of local inhabitants and a defensible position—the peninsula is surrounded by two rivers and Chesapeake Bay—made it ideal from an English perspective for the planned location of Fort James.

Jamestown, Virginia was settled on a swampy peninsula in 1607, making it America’s first permanent English colony. The soggy ground was considered un-farmable by the local Powhatan native tribes, and was rife with malaria-carrying mosquitos. But the lack of local inhabitants and a defensible position—the peninsula is surrounded by two rivers and Chesapeake Bay—made it ideal from an English perspective for the planned location of Fort James.

Initially, interactions between the local Powhatan tribes and the English were good—the natives provided food and hoped to continue to do so in trade for European metal tools. But the English, finding that the land truly wasn’t suitable to farm, especially after 1608’s poor harvest, couldn't produce enough food on their own. They attempted to force the natives to provide more food than they had even for themselves. The resulting conflict led to native raids on the fort and, eventually, to the Anglo-Powhatan War of 1610-1614.

The winter of 1609-1610 was especially brutal, and is referred to as ‘the starving time’ in historical records. The lack of food, ravaging disease, and attacks by the Powhatans led to dire conditions. By the time help finally arrived in May of 1610, only 60 of the original 500 colonists were still alive, and the fort was less of a military installation than a charnel house.

Writings of the time tell of cannibalism in the colony—including a husband who murdered his pregnant wife, and then salted and ate her flesh, a crime for which he was later executed. But no recovered remains provided evidence to support these tales. Until last week.

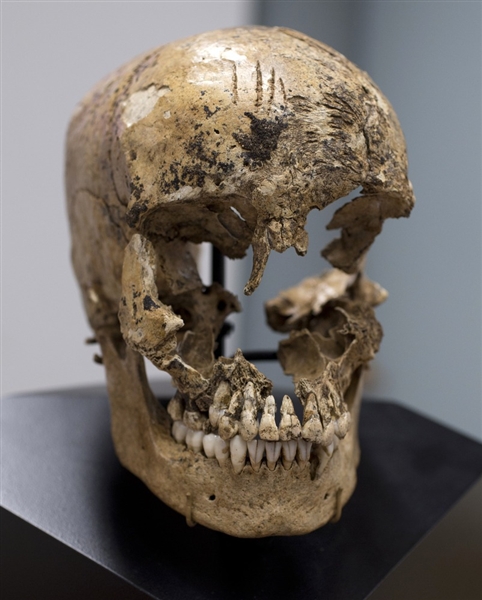

Archeologists were excavating what was essentially a 17th century garbage heap in the a cellar of a dwelling inside the remains of the fort when they unearthed a human cranium, lower jaw and some shattered leg bones scattered among horse and dog bones. Dr. Doug Owsley, a forensic anthropologist with the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History was called in to examine the remains. Long-time readers of this blog may remember Dr. Owsley as the forensic anthropologist who examined the remains of the unknown Union solider discovered in 2008 at Antietam. For the first time, Dr. Owsley was able to substantiate historical records, describing the discovering as ‘very strong evidence’ of cannibalism.

Kerfs from several tools are clearly visible on the bones of the skull. Chops from a hatchet or axe tentatively score the forehead, and then more substantially mar the back of the head as the attacker gained confidence and used more force. Knife marks on the cheeks and jaw show where muscle was sliced from the bone. The left side of skull is missing—tool marks from a pry bar on the remaining bone attest to the fact that the cranium was shattered when it was forced open to extract the brain. Blessedly,the regular nature of the kerf marks reveal that there was no struggle; most likely, the victim was already dead.

Forensic anthropology reveals clues about the victim of this horrific act—she was young, probably about fourteen years of age from the analysis of the skull, teeth, long bones and from epiphyseal fusion at the knee joint. Strontium analysis of the bone has determined that she grew up in England and arrived in America mere months before her death. She likely died of starvation or sickness in the first months of 1610, and, shortly thereafter, met her final fate at the hands of another colonist. Researchers have christened her ‘Jane’.

Most colonies did not last for even a year in the New World, so, in many ways, Jamestown is a story of persistence and survival during the worst of times. Sadly, it was at the cost of too many lives, some of them lived in desperation as the few remaining colonists struggled to hold on at all costs, buoyed by the faint hope of spring and the sight of a supply ship on the horizon.

Photo credit: Carolyn Kaster/AP

Complete!

Complete! Planning

Planning