Zika: Emergence of a New Epidemic

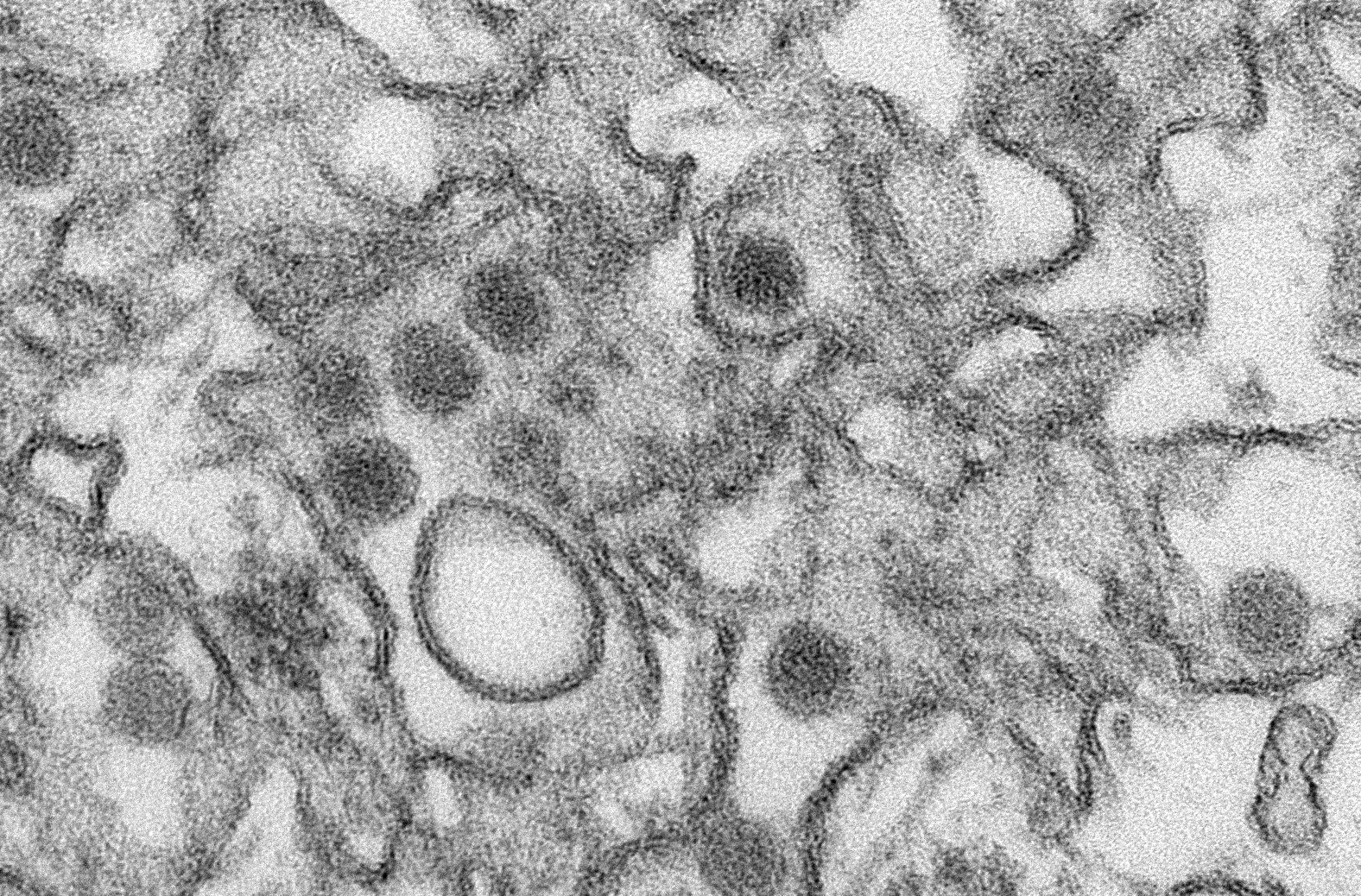

/Electron micrograph of Zika virus particles.

You’d have to be living under a rock for the last few weeks to have missed the fact that a new virus—called Zika—has been making headlines. In reality, Zika is not a new virus at all, however its effects in the last six months in Brazil and other south American countries has been utterly alarming. Worst, one of its most terrible of its outcomes strikes the most fragile of us—unborn infants.

The Zika virus was discovered in 1947 in the Zika Forest in Uganda. It is one of a number of viruses in the Flaviviridae family which includes dengue virus and West Nile virus. By far, the main method of transmission is via the mosquito Aedes aegypti, therefore the areas of mosquito-borne Zika infection follow the natural distribution of Aedes aegypti in an equatorial band around the planet. Historically, disease caused by Zika has been considered mild and mostly trivial with four out of five infected people never knowing they were ever infected. Those who develop symptoms usually present with a low grade fever, joint and muscle pain, and headaches lasting from approximately two to seven days. Since there is no effective medicine or vaccine, symptoms are treated directly—rest, plenty of fluids, and acetominophen to ease the aches and pains. For most patients that is sufficient, and severe disease and death were extremely rare.

However, a disturbing picture emerged from Brazil last November when the news broke that 4,000 babies had been born in 2015 with microcephaly—a birth defect in newborns with abnormally small heads and incomplete brain development. Compared to the normal average of 150 babies born with microcephaly in a single year, this is a staggering increase. While we’re still waiting for definitive evidence that this increase is due to the Zika virus, Zika was first identified in the country in May of 2015, and some pregnant women at the time showed evidence of the virus’ RNA genome, leading public health officials to infer that Zika was responsible. Late last week, Columbia reported three people who died of Guillain-Barré syndrome—a disorder where the body’s immune system attacks the peripheral nerves causing muscle weakness and paralysis—following Zika infection.

Recently, the World Health Organization took the significant step of defining Zika as a ‘Public Health Emergency of International Concern’. However, it is difficult to make recommendations about Zika since the virus is not well studied. Less than 200 scientific papers mention Zika, only a handful of which are notable for significant information. And the fact that so much is still unknown—all methods of transmission, life cycle of the virus, where it replicates inside the body, and what body fluids it can be found in and for how long—ties the hands of public health officials who are trying their best to prepare people on how best to protect themselves. The virus has been found in saliva, blood, semen, and urine, leading to warnings about sexual transmission, pregnant woman kissing anyone other than their partner, and to blood banks setting restrictions on blood donations in a window following travel to Zika-ravaged countries. Some countries, like El Salvador, have even suggested to women that they refrain from getting pregnant for the next two years, a difficult issue in a Catholic country where most methods of birth control are forbidden. At this point, the main preventative strategy is to avoid travel in the twenty-six countries with documented Zika infections. If not, avoidance of mosquito bites is the next best thing, by using bug spray, wearing long sleeves and pants to cover the skin, and sleeping in rooms with window screens or air-conditioning.

This story has struck a personal note in my day job as a manager of an infectious diseases lab. Flaviviruses are one of our main areas of study, with past projects including major NIH studies of both West Nile and dengue fever. In fact, dengue virus is carried by the same mosquito as Zika, opening up the possibility of co-infection or super infection (infection of a second virus following infection of the first). While the West Nile study was of North American cases, the more recent dengue fever study involved cases and controls from Central and South America and southeast Asia. Currently, we’re looking at the tens of thousands of samples in our freezers from that study and wondering how many of them might also contain Zika. Discussions are already well under way and we hope to join the fight against Zika very soon. We’re certainly better situated to hit the ground running than most labs considering our existing sample bank, and we have high hopes that we can make a meaningful contribution.

So where do we go from here? First and foremost, remember all the public health agencies are doing their best to keep people safe. It’s a damned if you do and damned if you don’t situation—people will be upset if recommended precautions seem too severe, or if they turn out to be too lax as additional information is discovered. They’re doing their very best based on extremely limited information. And while for the majority of people, Zika is not likely to be a major health concern, for the sake of those that are more significantly affected, it behooves us all to be diligent to protect the vulnerable.

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Complete!

Complete! Planning

Planning