The Legacy of Mississippi Asylum Life… and Death

/In 2013, while constructing a road on campus at the University of Mississippi in Jackson, workers uncovered sixty-six previously uncharted coffins. Work stopped to allow their removal to the university’s archeology center and the administration considered the matter closed. Then in 2014, during construction of a parking garage, approximately two thousand additional coffins were identified using ground penetrating radar; and the university realized it had a much larger issue on its hands. Now, three years later, the university administration believes it has finally discovered the scope of the bodies buried on campus after a larger radar investigation identified more than 7,000 coffins buried in twenty acres of land. Where did the bodies come from and how will the university deal with so many dead?

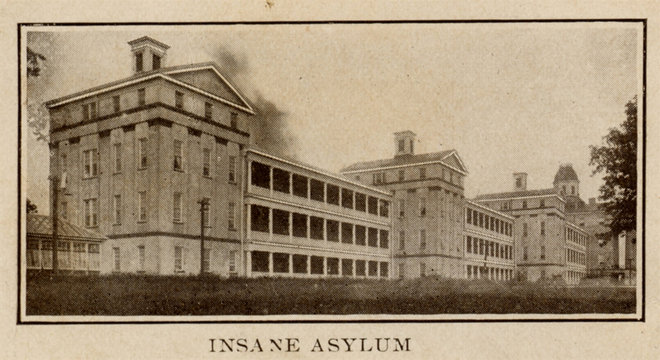

The source of the bodies is clearly based in the history of the area—the site was the location for the Mississippi State Lunatic Asylum, later called the Insane Hospital, which opened in 1855 and functioned until its closure in 1935. That hospital was later torn down to allow for the building of the current University of Mississippi Medical Center. People suffering from mental illnesses such as depression and schizophrenia were sent to live at the asylum where they could be treated as medical knowledge of the time dictated. Thousands died while still in the care of the state, and if their bodies were not claimed by family, they were buried in unmarked graves to the east of the asylum. The hospital kept records, and while some still remain, many are lost to history. While hand-drawn maps from the nineteenth century suggested the possible location of the cemetery, they did not indicate the scale—so the sheer size of the cemetery was a surprise to the university administration.

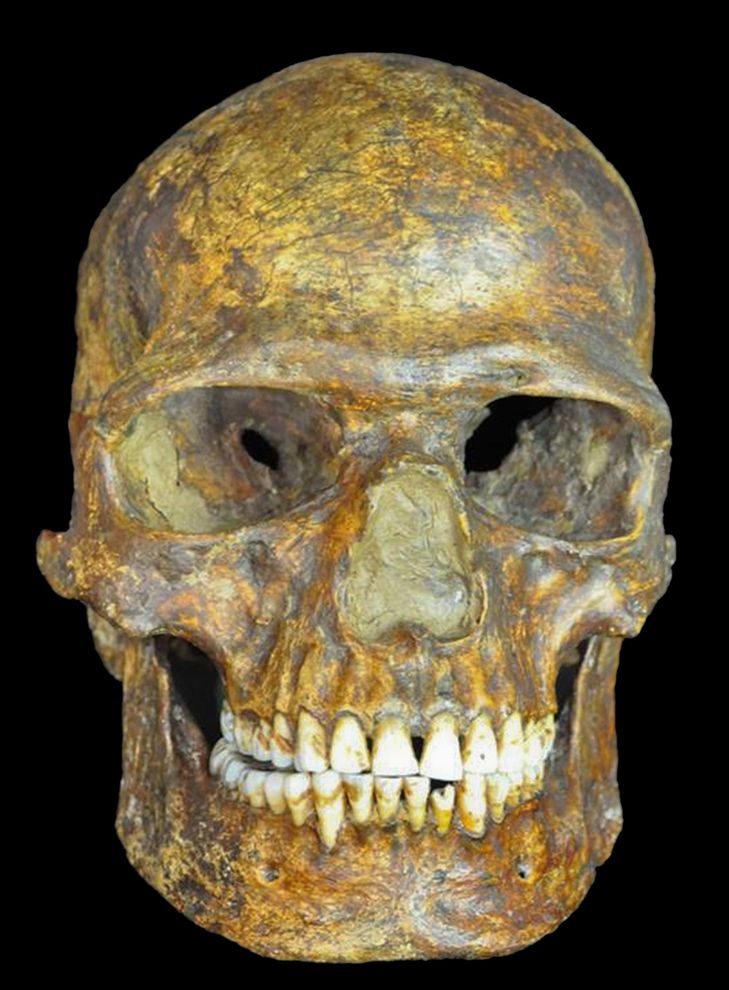

While the university is thrilled with the archeological and forensic treasure trove, practicalities must be considered. The cost of excavating over 7,000 coffins and reburying the remains is immense—an initial estimate placed it around $21,000,000 (approximately $3,000 per body). But the university plans to do the excavations in-house with their own Department of Anthropology, bringing the cost down to just over $3,000,000 over eight years. They intend to open a memorial and a new visitor center to highlight the history of the asylum, institutionalization, and healthcare in the pre-modern period. There are also plans to open a lab to study the remains.

Researchers hope to shed light on the institution itself and their methods of treating mental illness. Previous to the asylum, those suffering from mental illness were often jailed or kept prisoner in attics. Life in the asylum was likely not much easier, and the institution’s nineteenth century death rate averaged over twenty percent each year. Despite this, its population soared by 1900%—from approximately 300 patients in the late nineteenth century to the early twentieth century when it housed 6000 patients at its zenith. When the hospital closed, the patients were relocated to the state hospital in Whitfield, which is still open today.

There is a lot of personal interest within this discovery as well. Mental illness was so stigmatized in the past that suffering relatives simply ‘disappeared’ when they were shipped off to facilities such as the Mississippi State Lunatic Asylum. Within the local community there is a movement for possible descendants to donate DNA for comparison to the DNA of the remains in hopes of finding some of their own past.

Photo credit: University of Mississippi Medical Center

Complete!

Complete! Planning

Planning