Forensics 101: Sexing an Unidentified Victim Based on Skeletal Markers – The Pelvis

/

It’s a situation that occurs all too often ― the remains of a victim are found, but all that’s left is an unidentified skeleton. How can police solve this mysterious death if they don’t even know who the victim is? Several key pieces of information are needed to identify a unknown victim ― sex, age, race and time since death ― but without flesh or identifying documents, how can any of this be established?

A forensic anthropologist can determine this information given nothing but the skeleton itself. It may look like smoke and mirrors, but really it’s all about knowing which small details to look for. Add up those small details and a convincing picture appears, and, hopefully, a reliable piece of information can be added to the missing pieces of the puzzle.

So what are the details a forensic anthropologist looks for?

When it comes to sexing an adult victim solely from skeletal markers, the pelvis remains the most reliable feature. Pelvic sexing of children and preteens can be very difficult due to the lack of difference between the sexes before maturity.

There are several specific physical characteristics in the pelvis that are different between the sexes:

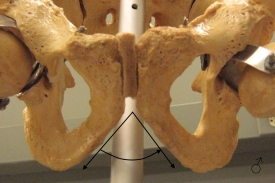

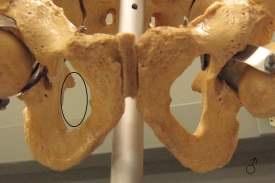

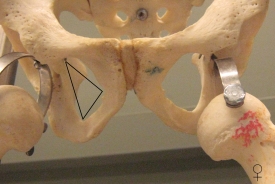

- Subpubic angle – The angle formed by the joining of the two halves of the pubis at the front of the pelvis. The angle is narrow in males and wider in females; this is partly due to the shorter pubis in males and elongated pubis in females.

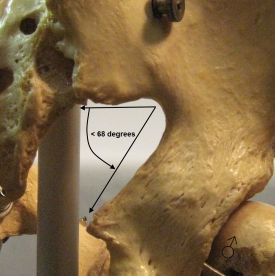

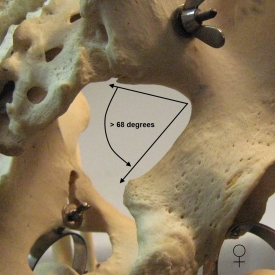

- Greater sciatic notch – The notch in the back of the hipbone that allows muscles and nerves to pass through the bony pelvic region. The notch tends to be narrow in males (less than 68o) and wider in females (more than 68o).

- Orbaturator foramen – The hole made by the joining of the ischium and pubis bones in the pelvis that allows nerves and muscles to pass through. It tends to be more oval in shape in males and more triangular in females.

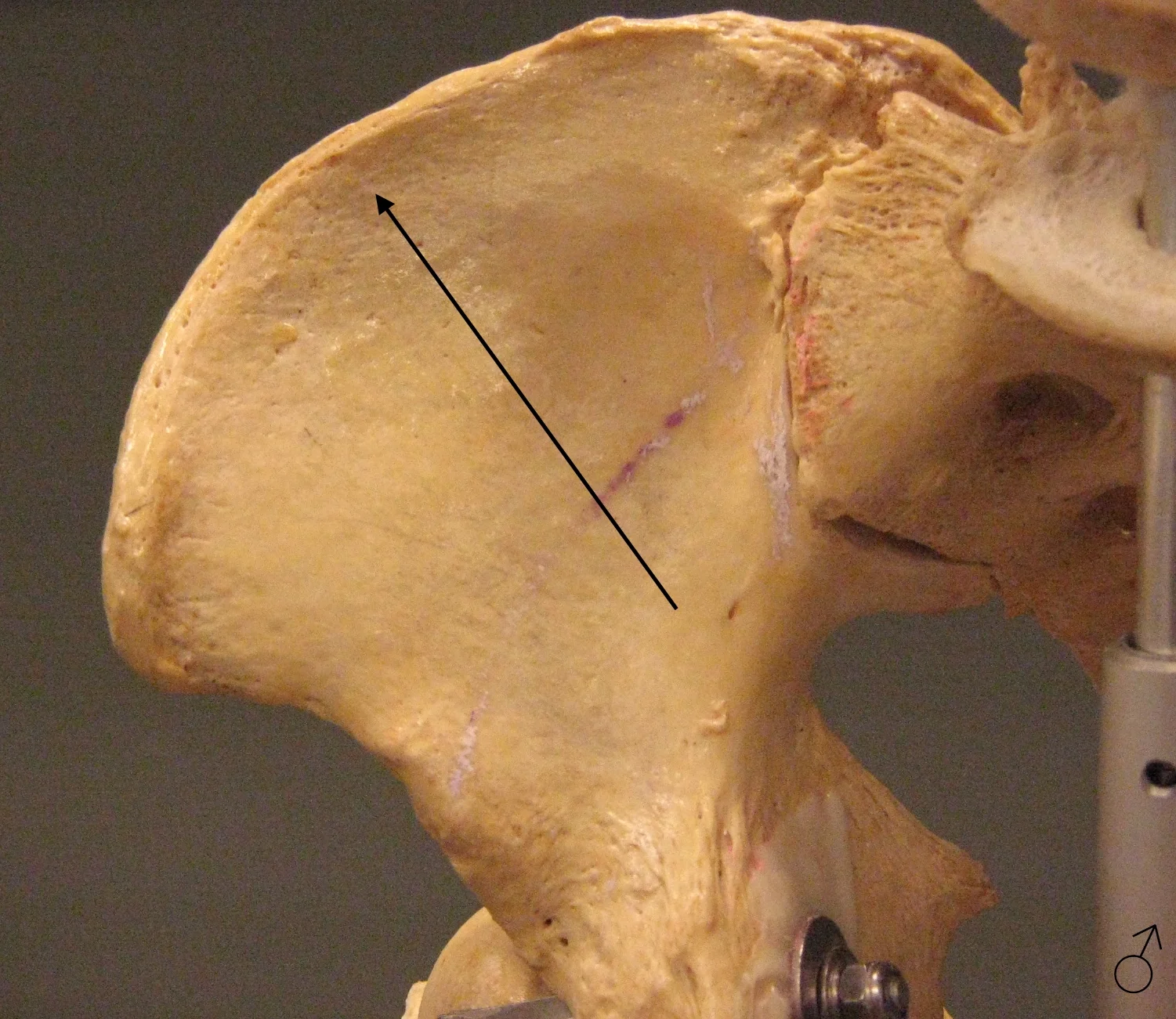

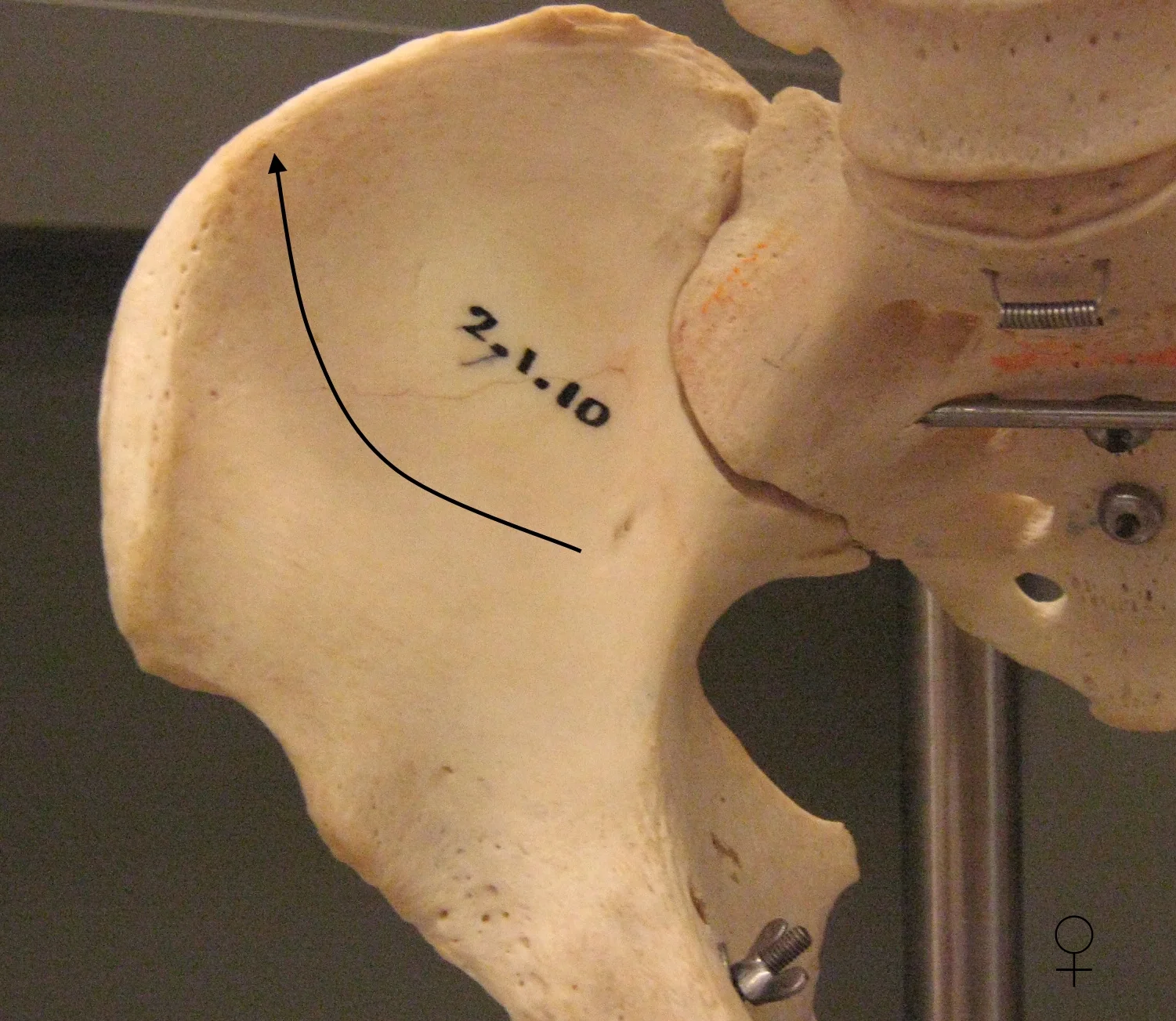

- Blade of ilium – The ilium is the largest of the three bones in the pelvis; commonly referred to as the ‘hipbone’. It is more flat and vertical in males and more flared or cupped in females.

Because of variation between people, some of these sex differences might be more or less pronounced, so the use of multiple markers is crucial. Better yet is using multiple skeletal elements (if they are available) to confirm the estimate. In our next Forensics 101 post, we’ll look at how to determine sex of a victim based on the skull.

Thanks to the McMaster University Department of Anatomy for providing skeletal specimens.

39.2%

39.2%