Guest Post: Putting faces on the dead – in fact and in fiction

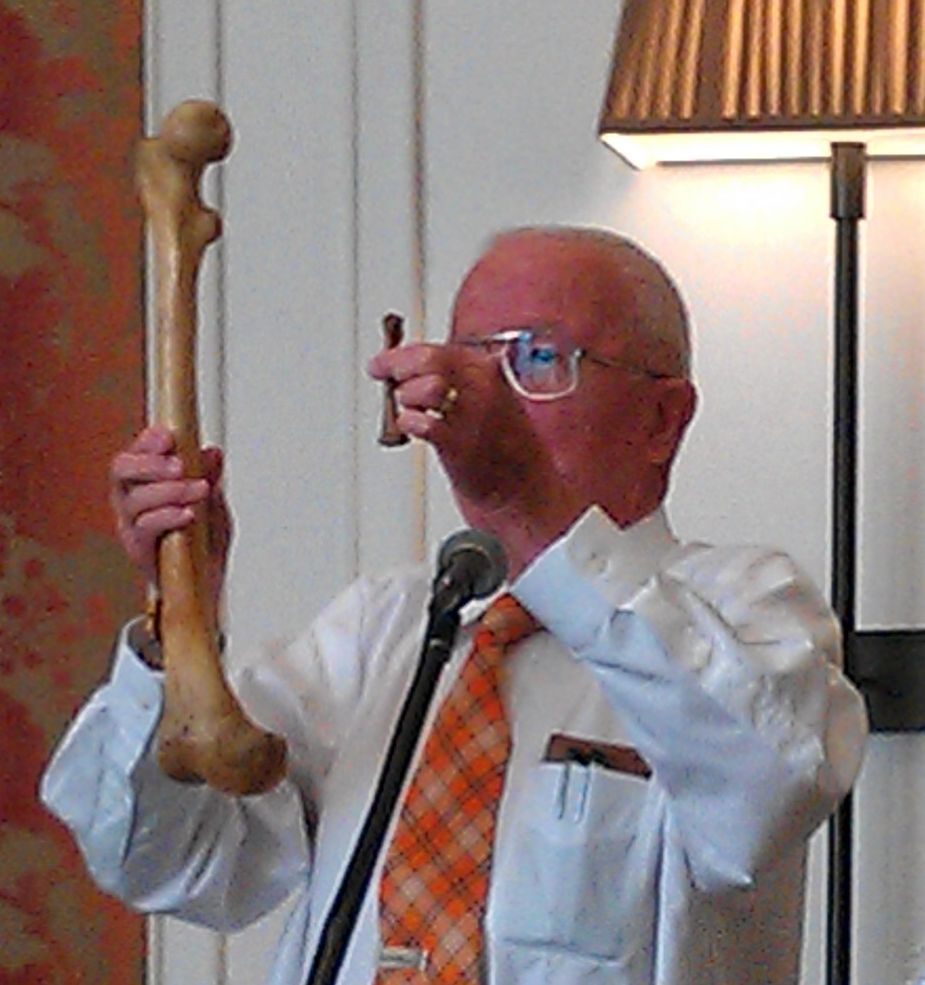

/Over the last few weeks, we’ve been focusing on the University of Tennessee’s Body Farm – how it was conceived and some of the research that’s been done there. Today we have a guest post by Jon Jefferson – the “Jefferson” half of the crime-fiction duo Jefferson Bass. Working in collaboration with Dr. Bill Bass, the forensic anthropologist who founded the Body Farm, Jon writes the bestselling series of Body Farm novels. The latest—The Inquisitor’s Key—comes out May 8.

Take it away, Jon…

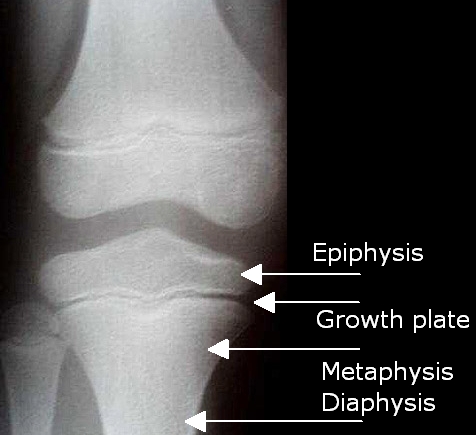

One of the hallmarks of the Body Farm novels is that the fiction incorporates realistic and detailed forensic techniques. The new book, The Inquisitor’s Key, is no exception. One of the techniques that’s used is radiocarbon dating—also called carbon-14 dating, or C-14 dating. In the book, our heroes, Dr. Bill Brockton and his assistant Miranda Lovelady, use C-14 dating to determine the age of an ancient skeleton that’s found hidden in the Palace of the Popes in Avignon, France. C-14 dating works by counting the isotopes, or atomic variations, of carbon within a sample, then comparing the sample’s carbon ratio to the ever-changing ratio in earth’s atmosphere during the past 10,000 years (a ratio whose changes have been recorded in tree rings – how cool is that?!). Think of C-14 dating, then, as atomic fingerprint-matching or handwriting analysis: match the sample’s fingerprint, or signature, to the atmosphere’s at a specific point in the past and presto, you’ve found the age of the sample.

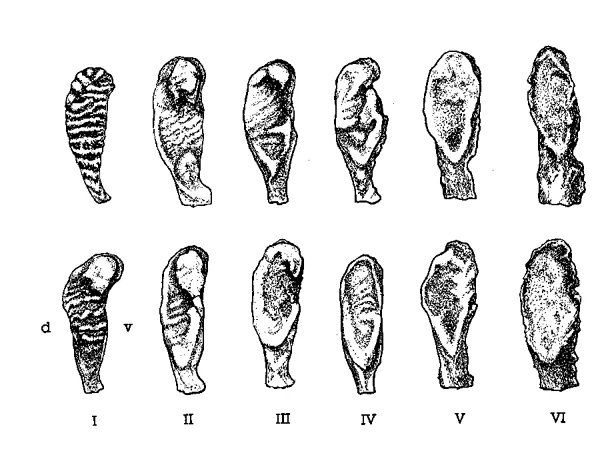

Another technique that comes into play in The Inquisitor’s Key is forensic facial reconstruction: an artist’s recreation—in clay or on computer—of the face that once existed atop the foundation of an unknown skull. In real life, Dr. Bill Bass and I once used that technique in a particularly puzzling case. A skeleton found in the woods in East Tennessee in 1979 had been tentatively identified by a medical examiner as that of Leoma Patterson, a woman who’d gone missing from a neighboring county five months earlier. That was back in the days before DNA testing, mind you, and the missing woman had no dental records to compare with the skeleton’s teeth. As a result, the identification wasn’t definitive, and some of the family doubted it. Eventually, they asked Dr. Bass to exhume the body and obtain a DNA sample, so they could be sure. He did, and the sample came back negative: according to the DNA lab, the body in the grave was not that of Leoma Patterson. That raised an interesting question: If it wasn’t Leoma, who was it? In an effort to find out, Dr. Bass and I commissioned Joanna Hughes, a talented forensic artist, to do a facial reconstruction on the skull. She did, and—to our astonishment—the clay face Joanna created bore a striking resemblance to the best photo we had of Leoma Patterson. Was it possible that the DNA lab had erred, and that the skull really was Leoma’s? To learn about this case, check out our nonfiction book, Beyond the Body Farm.

But I digress. Here’s an excerpt from The Inquisitor’s Key—a passage where Dr. Brockton recruits a forensic artist to do a facial reconstruction on the ancient Avignon skull (actually, on a scan of the skull, taken by a French x-ray tech, Giselle). By the way, the forensic artist in the following passage, Joe Mullins, isn’t just a fictional character; he’s actually a real-life forensic artist, doing the great work attributed to him in the excerpt. Thanks, Joe, for agreeing to a cameo in the novel!

Joe Mullins was three thousand miles to the west of France, but ten minutes after Giselle scanned the skull in Avignon, Joe was looking at it in Alexandria, Virginia.

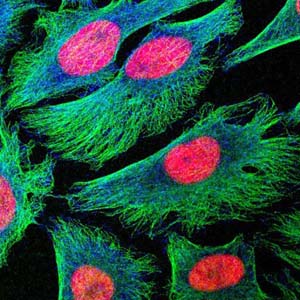

Joe was a forensic artist at the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, a mouthful of a name that he mercifully shortened to the acronym NCMEC, pronounced “NICK-meck.” After a traditional fine arts training in painting and drawing, Joe had taken an unusual detour. He’d traded in his paintbrushes and palette knives for a computer and a 3-D digitizing probe; he’d forsaken blank canvases for bare skulls—unknown skulls on which he sculpted faces in virtual clay. By restoring faces to skulls, Joe could help police and citizens identify unknown crime victims.

Joe wasn’t looking at the actual skull, of course. After the CT scan, Giselle and Miranda had uploaded a massive file containing the 3-D image of the skull and sent it to a file-sharing Web site—a cyberspace crossroads, of sorts—called Dropbox. Joe had then gone to Dropbox and downloaded the file, and, as the French would say, voilà.

The case clearly didn’t involve a missing or exploited child, so Joe couldn’t do the reconstruction on NCMEC time. But he was willing to do it as a moonlight gig, a side job, and when I’d first e-mailed to ask if he’d be able to do it—and do it fast—he’d promised that if we got the scan to him by Friday afternoon, he’d have it waiting for us first thing Monday.

My phone warbled. “Hey, Doc, I’ve got him up on my screen,” Joe said. “What can you tell me about this guy?”

“Not much, Joe.” I didn’t want to muddy the water by telling him what the ossuary inscription claimed. “Adult male; maybe in his fifties or sixties. Could be European but might be Middle Eastern.”

“Geez, Doc, that doesn’t narrow it down much.”

“Hey, I didn’t include African or Asian or Native American,” I said. “Give me at least a little credit.”

“Okay, I give you a little credit. Very, very little.”

“You sound just like Miranda, my assistant. Way too uppity.”

He laughed. “This Miranda, she sounds pretty smart. She single, by any chance?”

Sheesh, I thought. “Take a number,” I said.

For another sneak peek of The Inquisitor’s Key, grab 34 seconds worth of popcorn and watch the video trailer:

Also, you may now download the 99 cent e-story prequel to The Inquisitor’s Key entitled Madonna & Corpse, which came out today! Read an excerpt of Madonna and Corpse on Jon Jefferson's blog.

39.2%

39.2%