Last week, we talked about the science of space archeology, and how, with the help of high resolution satellite scans taken 400 miles above the earth, a well-trained and intuitive eye can discern archeological sites hidden on the earth’s surface. This week, we’re going to talk about Dr. Sarah Parcak’s latest amazing discovery based on this technology.

The Vikings were a group of Scandinavians, first known for their international trading, but later known universally for their violent raiding of other lands and cultures. They were groundbreaking nautical engineers for the time and their carefully crafted vessels allowed them to travel from present day Norway, Sweden, and Denmark to Britain and Scotland, Russia, Turkey, Iran, and even all the way to North America.

The Vikings used water to move between locations, be it rivers to move through Europe proper or the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea to go further. Starting in the 8th century, they set out to trade with peoples in other lands, but quickly learned that it was more successful and lucrative to simply raid those lands instead. They spread across the north Atlantic, moving from Scotland to Iceland, and then to Greenland.

But how did they so successfully set off into the unknown, and not be lost forever at sea? The Vikings were not only expert naval engineers, but were also expert navigators. They learned how to be able to detect land up to 50 or 60 miles away, simply by watching distant clouds, identifying sea birds out for a day of fishing, or by the smell of grass and other plants, carried by the strong sea breezes.

One of the great Viking explorers was Erik Thorvaldsson, better known as Erik the Red. Erik was part of an Icelandic settlement before he was exiled for three years in 982 A.D. after he murdered several members of the settlement. He and his men set sail, only to discover Greenland. It was Erik’s son, Leif Erikson, who is credited with the discovery of North America. He and his men sailed from Greenland, but were caught in a storm and driven due west, where they discovered a previously unknown coastline. Scholars studied the Viking texts of the time and believe Erikson found Baffin Island in Canada. From there he sailed south, down to Labrador, and then to Newfoundland.

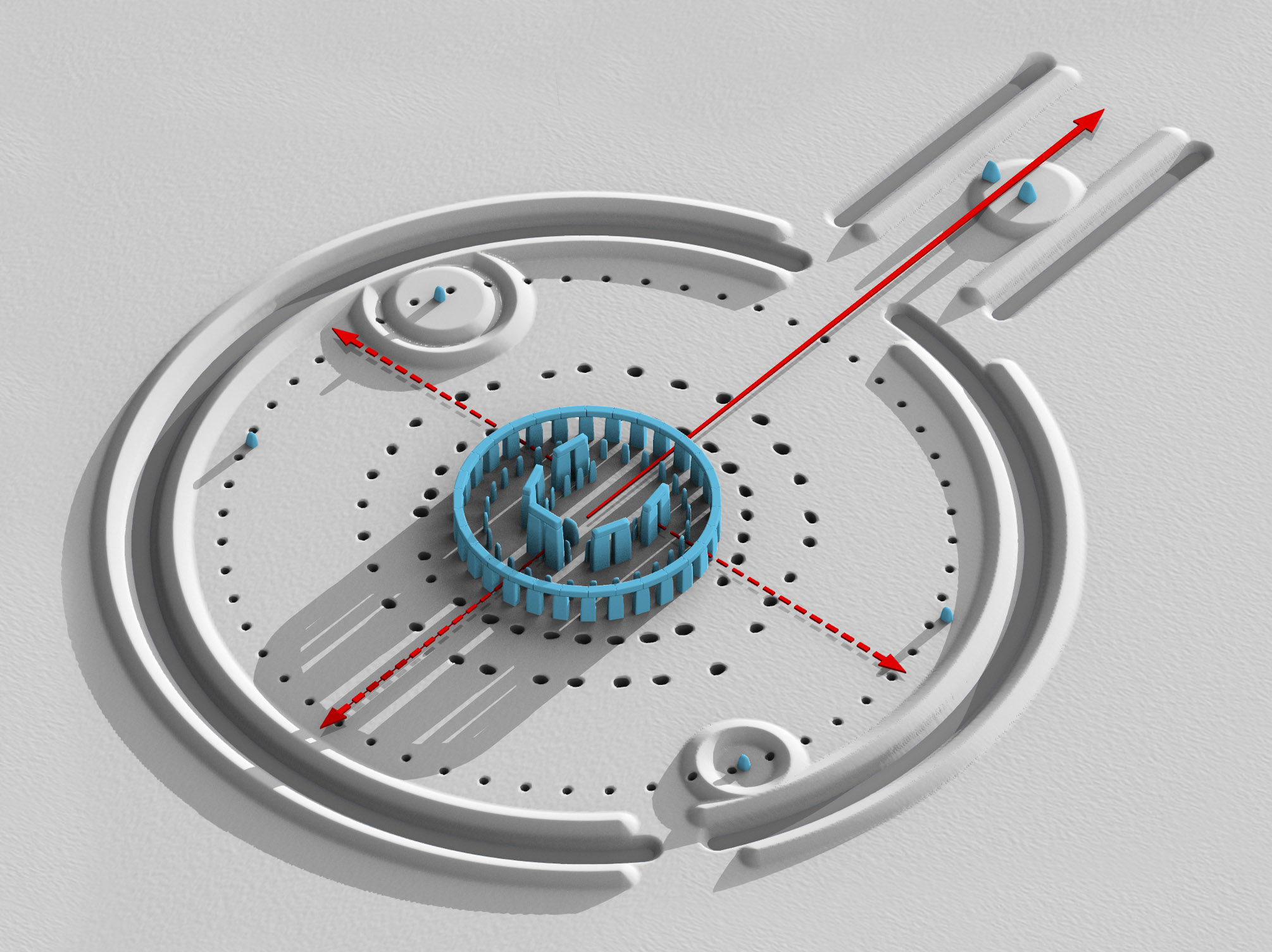

In 1960, the only officially designated North American Viking settlement was discovered in northern Newfoundland. Archeologists called it L’Anse Aux Meadows, and found there the foundations of traditional Viking longhouses for approximately 90 people, and traces of metal works, a technology native Canadians did not have at the time. But archeologists also found something they could not explain—seeds from a plant that only grew hundreds of kilometers south of that site, leading them to believe that there must have been at least one other settlement south of L’Anse Aux Meadows.

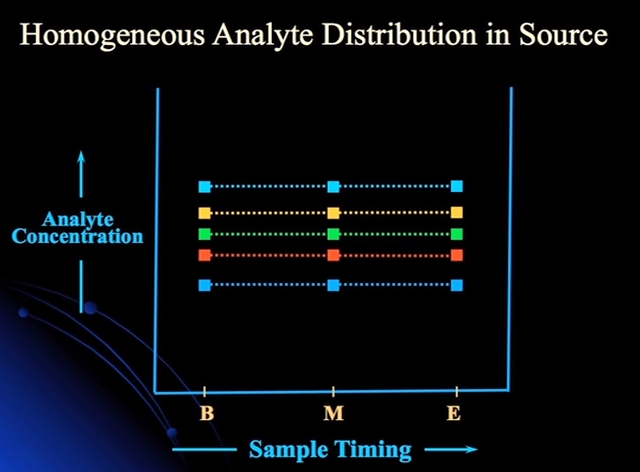

Dr. Sarah Parcak, an archeologist at University of Alabama at Birmingham and the director of the Laboratory for Global Observation, took on the challenge of trying to find this new settlement. Using the Worldview satellite that resolves images down to 10”, she examined the Newfoundland coastline. To do this, she studied near infrared scans after processing them for false colour to pick up differences in the vegetation—indications of decreased health of plants visible in the near infrared frequency could indicate the presence of foundations or other man-made objects below the surface.

Dr. Parcak found a potential site at Point Rosee, Newfoundland. Located on the west-facing coast on the southern edge of Newfoundland, it lies 370 miles southwest from L’Anse Aux Meadows. Among other possible structures, she identified a rectilinear shape with the same dimensions as a longhouse found at L’Anse Aux Meadows. This was a very strong indication that Point Rosee could be a related archeological site.

The first step for Dr. Parcak’s team was to do a non-invasive survey of the area, which they accomplished using a magnetomer to detect subtle differences in magnetism of the scanned soil. The magnetomer will not only indicate the presence of metals but it will also provide evidence of burning or soil disturbances. A number of ‘hot spots’ were discovered and compared to the satellite scans. It was this successful comparison that earned the team a two week test excavation to see if the they could find any physical evidence of a Viking settlement.

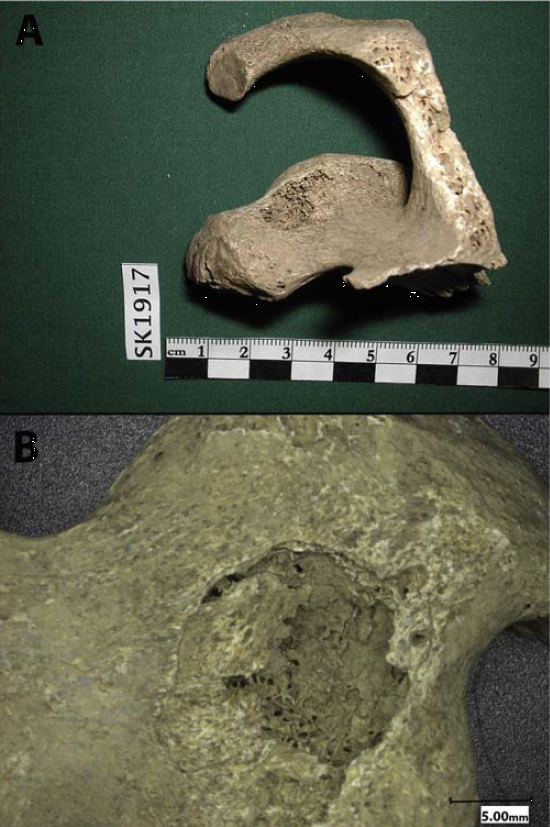

After surveying and gridding off the area to match the terrain exactly to the satellite images, the team dug several test trenches. It was backbreaking, muddy work, but they discovered several items of interest: some seeds, possible fragments of metal work, some clumps of what the team thought might be slag (a byproduct of metal work and a significant indicator of Viking activity), and darkly striped soil seen before in other Viking sites from their use of slabs of turf to insulate buildings.

In the end, the seed was determined to be from the 17th century and archeologists had to admit it could have filtered down into the extremely moist soil hundreds of years later. But it was the suspected slag that ended up as the crucial evidence. While it wasn’t actually slag—it was fire roasted bog ore—it represents a step in preparing ore for metalwork and is indicative of the presence of a group of people with skills different from the resident aboriginals of the time.

It is this single piece of evidence that will now set the course for future excavations. It is a very strong possibility that a Viking settlement occupied Point Rosee over a millennia ago, a full 500 years before Columbus sailed west to ‘discover’ a land found and temporarily settled by other Europeans centuries before. Dr. Parcak and her team hope to shine a light on a time period that is still mostly a mystery, expanding on the history of a new land, as well as the saga of a lost people.

Photo credit: Kenny Louie

COMPLETE!

COMPLETE! Planning

Planning